Katerina Gkoutziouli

Despite the fact that new media art might be still treated as a new and recent phenomenon of art practice, the story of new media can be traced back as early as the sixties. Artists such as John Cage, Allan Kaprow, Roy Ascott, E.A.T. have been preoccupied with themes including interaction, multimedia, electronics, kineticism, cybernetics and technology, and so have curators and theorists such as Marshall McLuhan, Jasia Reichardt, Lucy Lippard and Jack Burnham, among others. The context for artists, theorists and curators alike has been changing since that time, when this type of work formed a new territory for exploration in the arts. There was not only a change in creative language, but also a change in aesthetics and attitudes that would effect the ways we perceive artworks, exhibitions and cultural production in general.

One of the landmark exhibitions was “Les Immatériaux” curated by Jean-Francois Lyotard at the Centre Pompidou, Paris in 1985. Lyotard had already written his seminal book The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979) in which he examined the changes in human condition effected by technological developments in communications, mass media and computer science. The exhibition sought to present the repercussions of such a restructure of society and culture and also to construct an emergent space filled with emergent concepts. Nathalie Heinich explains “Paintings and sculptures were still present, of course, but became part of a much larger set of information made up of signs, words, sounds and technical artefacts” in a labyrinth-like exhibition space. Additionally, the notion of “immateriality” was introduced at a point when computers and interfaces were not user-friendly, a fact that also highlighted the latent problematic aspects of technology in art making and curating. ∗ Curating here may have functioned as a philosophical quest authored by Lyotard, which in spite of its drawbacks has opened the door to a new era of exhibition making.

Moving forward to the mid-nineties, we can see the next wave of artists and curators engaging with new media under a new set of conditions again. Since the term “new media” is a very loose one, I would like at this point to refer to Olia Lialina’s description of new media: “a field of study that has developed around cultural practices with the computer playing a central role as the medium for production, storage and distribution”. However, it still seems that new media art cannot be contextualized under a certain canon because of its hybrid forms, and there is still a need for new media art practitioners – be they artists, curators, theorists- to provide a contextual umbrella for new media practices to be discussed.

From a curatorial perspective, new media art has brought new challenges to contemporary curating with its immaterial nature, its interactive qualities, its computer-based character and its constant developments. Anyone working with or keeping track of the shifts in new media will have noticed that new media art can be “web-based projects, sound events, virtual reality installations, mobile cellular, or PDA projects, and practices- conceptual art practices, networked-based practices, software coding or sampling” as Sarah Cook has outlined.∗∗ It is hard to permit the flexible and dynamic character of new media art to fully articulate in an exhibition space since most new media artworks tend to defy physicality. The need for new curatorial expressions to embrace the concepts of new media is becoming more and more apparent in the variety of exhibition formats.

Alexei Shulgin, Desktop Is (1997)

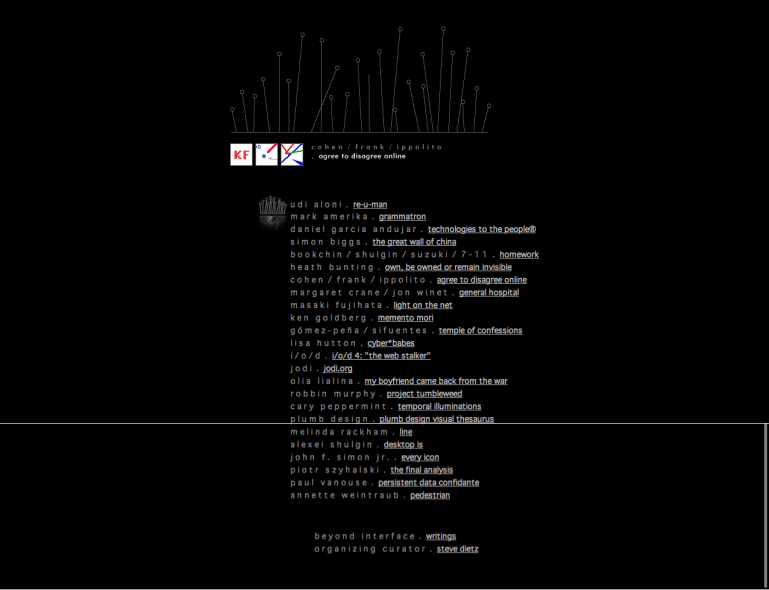

Curating in online contexts has been a prevalent mode for web-based art projects. A rewind through the recent history of new media art will remind us that the dawn of the World Wide Web proved beneficial to web artists not only because of the new possibilities of the medium, but also because it allowed a certain degree of autonomy from institutions and curators altogether. An early example of such an exhibition was the project Desktop Is (1997) initiated by artist Alexei Shulgin for which he gathered desktop screenshots from 67 artists and hosted them online for public viewing. The developments the World Wide Web brought about at that time were equally important for curators. The novel notion of distribution and communication meant that not only artworks could be distributed but also curatorial practice. The “instantaneity in contemporary culture” (Charlie Gere, 2008)∗∗∗ was and still is evident and emergent in many distributed artworks and exhibitions on the web. For example, the exhibition Beyond Interface (1998) curated by Steve Dietz at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. On the archival website of the exhibition, one can find Steve Dietz’s quote, which reads: “This online exhibition presents a simple proposition. There is art that is created to “be” on the Net. After that, it gets more complex very quickly. Beyond Interface explores some of the complicating issues but does not attempt a comprehensive investigation… the main goals of Beyond Interface are to present outstanding examples of net-based artistic activity, and to try and begin to better understand and appreciate this art and its context.” Steve Dietz is very conscious about his early venture by pointing out the uncertainties of curating web-specific exhibitions. Nevertheless, that is mostly the case when something new is coming out. By laying emphasis on the art and the context, Dietz attempts to highlight the dynamic of web-based artworks, being fluid and hybrid and also the Web as a space for art production, curating and cultural interaction. However, while distributed curatorial practice on the web might fulfill the democratic and decentralised expectations of its medium, it also could ensure the work is easily confined to a specialist audience online.

Beyond Interface, 1998 – Walker Art Center, curated by Steve Dietz

Beyond Interface, 1998 – Walker Art Center, curated by Steve Dietz

Curating new media art in “offline” contexts is another main method of presenting such work. From the eighties onwards, many different spaces and structures have flourished to support new media art activities. New media centres such as ZKM in Germany, The Banff Centre in Canada and FACT in England; festivals, like Ars Electronica and Transmediale; galleries such as the Furtherfield Gallery in London; and labs such as the V2_ Institute for the Unstable Media in the Netherlands, among others. Contemporary art museums have been quite wary of new media art, with some exceptions such as SFMOMA, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Baltic. Simply stated, the visibility of new media art exhibitions in museums is low compared to mainstream contemporary art shows. The exhibition Database Imaginary (The Banff Center, Alberta, Canada, 2004) curated by Sarah Cook, Steve Dietz and Anthony Kiendl included works from 1971 to 2004. The exhibition sought to explore the idea of the database as an evolving phenomenon in human culture, featuring works such as Hans Haacke’s “Visitors’ Profile” (1971), a questionnaire about contemporary events that was distributed to museum visitors to a group exhibition in Milwaukee and Graham/Mongrel’s “Lungs-London.pl” (2004), a Perl software-code poem based on the 1792 poem London by William Blake. Database Imaginary attempts to establish connections between old and new art forms that share a common ground. Such exhibitions provide a space, firstly, to reflect on the continuum of ideas taking “shape” through a range of mediums and secondly, to discover the correlations that new media art shares with its precursors. The idea of creating narratives that are not fragmentary and follow the trail of art development also shows the dynamic of curatorial practice itself. If museums refrain from showing new media art by being skeptical about the qualities of such art in the course of art history, then exhibitions, such as Database Imaginary, provide for the art references that institutions may lack.

There is no doubt that there is not a singular practice or canon of curating new media art and that is primarily triggered by the hybridism of the art itself. Christiane Paul (2008) has argued that ‘Because new media art is more process-oriented than object-oriented, it is important to convey the underlying concept of this process to the audience’.∗∗∗∗New media art curators need to be constantly resourceful in order to create evocative spaces and experiences. As new media art gradually enters the museum doors, curatorial strategies need not only communicate the art but also the fact that the exhibition itself is a process.

First published here: http://curating.info/archives/566-Curating-in-a-new-media-age.html

∗ See Nathalie Heinich (2009) “Les Immatériaux Revisited: Innovation in Innovations” at http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/les-immateriaux-revisited-innovation-innovations and Sarah Cook (2008) “Immateriality and its discontents. An overview of main models and Issues for Curating New Media” in Christiane Paul (ed). New media in the White Cube and Beyond. University of California Press, pp 26 – 49

∗∗ Sarah Cook (2008), “Immateriality and Its Discontents. An Overview of Main Models and Issues for Curating New Media”, in Christiane Paul (ed.), New Media in the White Cube and Beyond. Curatorial Models for Digital Art. Berkley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, p. 27

∗∗∗ Charlie Gere (2008). “New media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age” in Christiane Paul (ed.). New Media in the White Cube and Beyond. Curatorial Models for Digital Art. Berkley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, p. 23

∗∗∗∗ Christiane Paul (2008), “Challenges for a Ubiquitous Museum. From the White Cube to the Black Box and Beyond”, in Christiane Paul (ed.), New Media in the White Cube and Beyond. Curatorial Models for Digital Art. Berkley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press,p.65